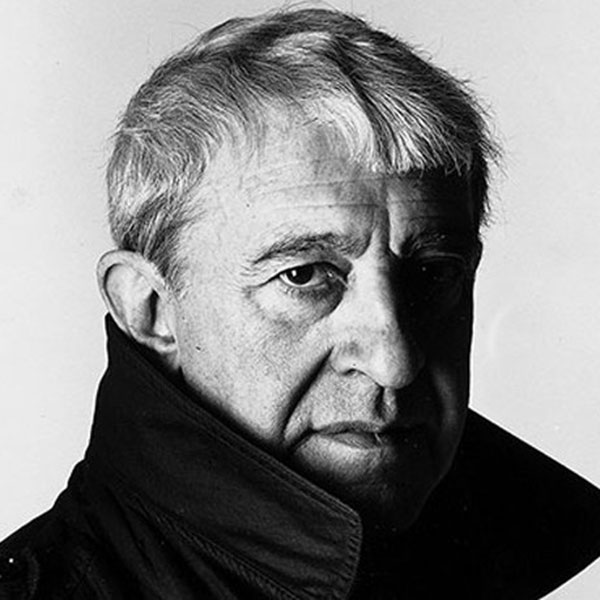

Kenneth MacMillan

Kenneth MacMillan was the leading ballet choreographer of his generation. He had a burning sense that ballet theatre should reflect contemporary realities and the complicated truths of people’s lives. He became director of The Royal Ballet and created some of the outstanding dance works of the twentieth century.

Born in Dunfermline, Fife on 11 December 1929, Kenneth was eleven when he won a scholarship to the local grammar school. During WWII, the school was evacuated to Retford in Nottinghamshire and it was here that he first discovered ballet. He had already learnt tap and Scottish country dancing and taken part in entertainments for soldiers at American air force bases.

Following his mother’s death in 1942, a dance teacher in Great Yarmouth, Phyllis Adams, became, in effect his surrogate mother. Realising she had a prodigiously talented pupil, she taught him for free and, in effect, shaped his ambitions.

When MacMillan was fifteen he was awarded a scholarship to the Sadler’s Wells School. In little over a year, he became a member of the Sadler’s Wells Opera Ballet (later Theatre Ballet). Soon he moved to the larger Sadler’s Wells company, now the Royal Ballet, based at Covent Garden.

MacMillan was increasingly troubled by stage fright which compelled his turning his hand to choreography. His early success with Danses Concertantes in 1955 was, in Clement Crisp’s words, “a declaration of talent, of the arrival of the new heir.”

The following years were intensely productive: In the 1960s MacMillan proved his vision to be essential to the identity of The Royal Ballet, first with the high theatricality of The Rite of Spring and then in 1965 with his definitive version of the Shakespeare/Prokofiev Romeo and Juliet, the work by which he is best known today.

Following great successes with Stuttgart Ballet for Song of the Earth and Requiem (to the Fauré score), MacMillan moved to West Berlin to become director of the ballet at the Deutsche Oper, remaining there for four years. In Berlin he created his multi-media Anastasia about a mental patient who claimed to be the sole survivor of the Russian Imperial family which was an important marker for later works such as Isadora and Mayerling.

In 1970 he returned to London to direct The Royal Ballet. Almost immediately MacMillan faced a financial crisis and was forced to lose some forty dancers from the strength of the two companies. Temperamentally, MacMillan struggled with the demands of administration. Nonetheless in his time as director he greatly expanded the company’s repertory, doubling the number of Balanchine works, introducing ballets by Tetley, Cranko, Van Manen, and Neumeier. Outstandingly, he persuaded Jerome Robbins to come to London to stage Dances at a Gathering.

In 1974 he created the three-act Manon, which became a repertory classic. In his concentration on long ballets MacMillan was exceptional: no twentieth century choreographers has produced so many full-length works – and on subjects which to some minds seemed alien to ballet.

1974 was also the year in which MacMillan married Deborah Williams, an Australian artist; the couple had a daughter, Charlotte.

After seven years as director of The Royal Ballet, he retired so that he could focus exclusively on his choreography, a decision triumphantly vindicated by Mayerling, which he made in 1978. Choreographically the richest of his three act ballets, it is a dark study in psychosis. Later works drew on a similarly dark palette; a disturbed family in My Brother My Sisters; fractious mental patients in Playground; Valley of Shadows includes scenes in a Nazi concentration camp.

Kenneth MacMillan was knighted in 1983 and in 1984, while remaining chief choreographer of the Royal Ballet, he became associate director of the American Ballet Theatre for some five years.

The final years of his life were immensely productive. After a serious heart attack in 1988 he knew he was living on borrowed time. After a five-year period in which he had not created a new work for Covent Garden, he returned in 1989 to make The Prince of the Pagodas, choosing the 20-year-old Darcey Bussell as his young heroine. For Dance Advance, a group of former Royal Ballet soloists, he created Sea of Troubles, a modern-dance version of Hamlet.

Kenneth MacMillan died at the Royal Opera House on a night when Birmingham Royal Ballet was presenting his Romeo and Juliet in Birmingham, and when Mayerling was being revived at Covent Garden after a long break. The curtain calls were cut short by the news that he had collapsed backstage. Six weeks later the National Theatre’s Carousel, for which MacMillan had choreographed the dances opened on the South Bank.

Sometimes in his lifetime it seemed as if his gifts were more valued in the wider world of the theatre than in the enclosures of classical dance. Since his death, however, his reputation has continued to grow. Audiences flock to his work, while dancers everywhere vie to perform in his ballets. Throughout his career he kept faith with his classical roots. He married it to a strong theatricality and, underneath it all, a deep moral sensibility. In Kenneth MacMillan’s hands ballet was not a fairytale art, but a powerful mirror to human frailty.